Kyle

Amstrong

Protection R&D Leader

13 décembre 2024

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between 2030 and 2050, climate change will contribute to approximately 250,000 additional deaths annually due to under-nutrition, diseases, and heat stress alone. In this article, Kyle Armstrong, Protection R&D lead, takes a closer look at the impact this is having on mortality.

As global climatic conditions evolve, we witness a surge in extreme weather events, including floods, droughts, wildfires, and extreme heat. Recent experience in the UK is conforming with this trend, with the 2023/24 winter making it into both the top 10 warmest and wettest winters since records began.

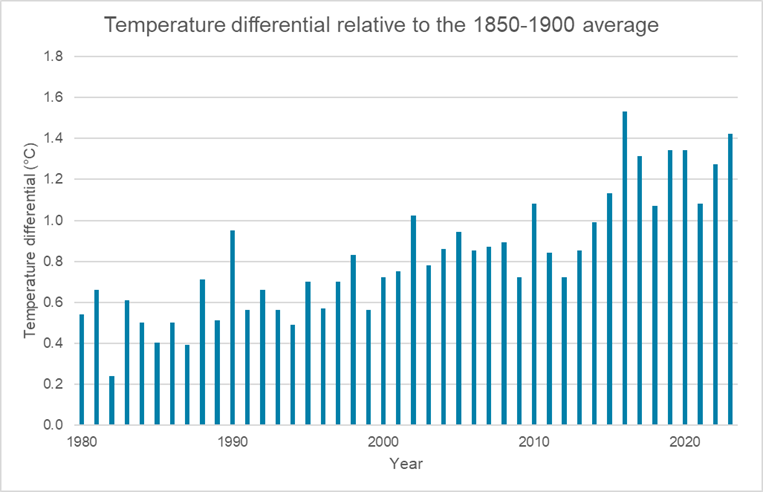

The 2015 Paris Agreement set a goal to limit the rise in global temperatures to less than 2°C above the average temperature during the pre-industrial era (1850-1900), which is before the widespread use of fossil fuels. This agreement also committed to make sustained efforts to achieve a rise below 1.5°C1, as this is a critical point above which global warming accelerates2.

Recent data suggests we are dangerously close to this; 2023 became one of the hottest years on record with global temperatures reaching 1.4°C above the pre-industrial average.

Source: National Centres for Environnent Information3

The impact of climate change on mortality is multifaceted. The World Economic Forum predicts that flooding will be the primary cause of additional deaths up to 2050, followed by increased drought4. Heatwaves are projected to become more frequent, and average temperatures are anticipated to rise overall. Winters are predicted to be milder, which could potentially enhance the transmission of diseases like malaria in tropical countries5.

This paper will focus on the direct effects of increased temperatures on the human body and how these changes influence mortality risk, before considering the implications for the UK and insured lives.

As covered in SCOR’s 2022 Expert View paper2, and demonstrated by epidemiological studies, elevated heat levels can lead to an increased incidence of cardiac arrest, heart disease, arrhythmia, and stroke6. While the precise mechanisms underlying this heightened risk remain partially unknown, it is evident that factors such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and heightened metabolic demands significantly strain the cardiovascular system7. Individuals with pre-existing heart conditions, including hypertension and heart disease, are particularly susceptible to further health deterioration in such conditions.

Moreover, higher temperatures are also associated with an elevated risk of respiratory diseases and mortality. Hot and humid air exacerbates the accumulation of harmful air pollutants, including ozone, which directly contributes to respiratory mortality8. Notably, this risk is more pronounced in urban areas compared to rural regions due to the elevated concentration of polluting particulates in the air9.

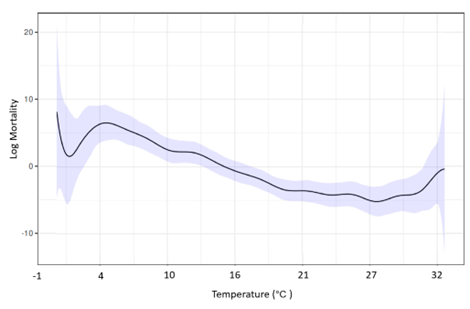

A recent study in collaboration between the SCOR Foundation for Science and the University of Melbourne investigated the connection between US average daily temperature and mortality rates between 1968 and 2018, as illustrated on the following graph:

Generally, mortality rates decrease in line with rising temperatures until approximately 28°C. Beyond this point, mortality begins to rise as cardiovascular stress becomes more pronounced.

Interestingly, the highest mortality rates occur when temperatures are close to freezing. Extensive research has explored the increased risk associated with extreme cold, which shares a similar mechanism of heightened cardiovascular strain10. Notably, an influential meta-analysis published in 2023 estimated that a 1°C decrease in temperature is associated with a 1.6% increase in cardiovascular risk11.

A small dip in mortality is evident on the graph just above freezing temperatures. Researchers suggest that this phenomenon may be attributed to more people staying at home, thereby reducing the risk of infectious diseases.

Furthermore, cool nighttime temperatures play a crucial role in aiding the body’s recovery from extreme daytime heat. A study conducted in Japan found that even after accounting for the daytime mean temperature, all-cause mortality increased by 9% following “tropical nights”, defined as periods when temperatures remained above 25°C12.

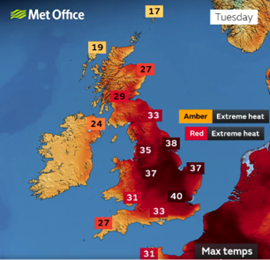

The Met Office predicts that the UK will experience warmer and wetter winters, hotter and dryer summers, and more frequent weather extremes such as storms and droughts13. Among these, summer heatwaves are expected to be the have the greatest impact to mortality.

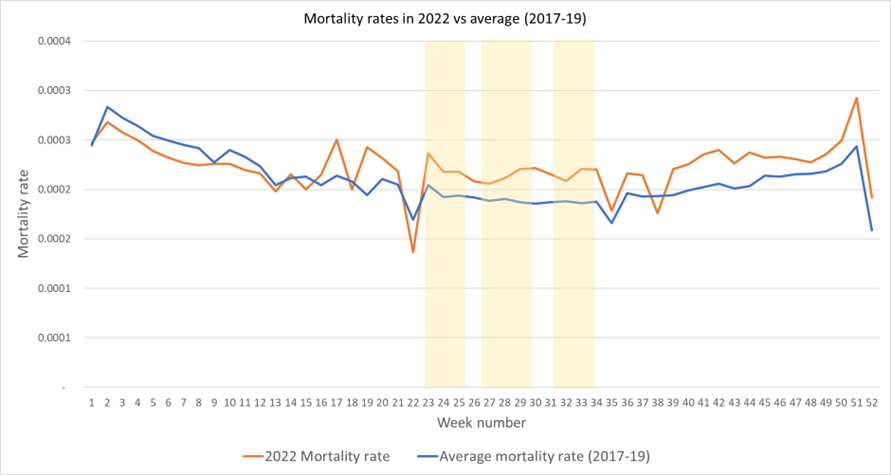

A common approach to measure additional deaths from heatwaves is to compare mortality rates over the heatwave periods with what we would expect based on a historical average.

In July 2022, UK temperatures reached 40°C for the first time and 2022 became the warmest year on record.

The graph below depicts the weekly mortality rates in 2022 compared to the average mortality rate between 2017 and 2019. The highlighted bars indicate the weeks during which heatwaves occurred.

Source: Office for National Statistics15

During these periods, there is a clear excess mortality. However, the challenge lies in attributing this excess solely to heat-related causes. Other factors, such as the strain on the National Health Service (NHS) and post-Covid sequelae (which also impact cardiovascular mortality), contribute to this excess. Consequently, identifying heat-related causes alone is difficult, especially when this elevated mortality persists throughout the winter of 2022.

The Office for National Statistics carried out a similar exercise and attributed 4,507 excess deaths to the 2022 heat waves. They also estimated that once temperatures reach 25°C, the number of temperature-related deaths increases by approximately 50%16.

One approach to overcome the distortion caused by excess mortality is to analyse heatwaves that occurred before the Covid-19 pandemic. Public Health England (PHE) conducted a study of the UK deaths during the summer of 2018, which included four separate heatwaves. This study estimated that 863 excess deaths in England in 2018 were due to high temperatures17. While this figure may seem significant, it represents only 0.1% of the total deaths that year. Furthermore, the impact would be even lower for insured age groups, as the report concluded that there was no excess mortality for ages under 65.

Insured lives are generally less affected by extreme heat compared to the general population. This is mainly because young children and the elderly, who are most vulnerable to temperature-related health risks, are underrepresented in the insured population. Furthermore, medical underwriting leads to a lower share of people with cardiovascular risk in the insured compared to the general population, evidenced by the fact that only 19% of insurance mortality claims are due to cardiovascular causes, relative to contributing 25% to overall deaths in the population (for equivalent ages).

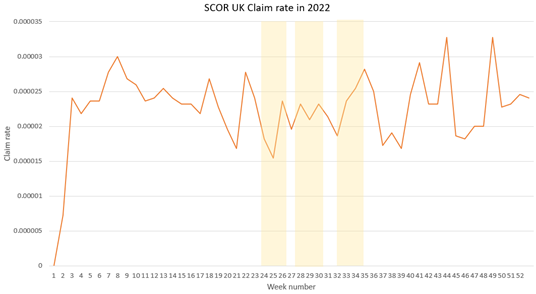

The graph below illustrates SCOR’s weekly claim rate in 2022.

Although weekly claim rates are volatile, there is no evidence of increased mortality during the heatwave periods for insured lives.

Climate change remains one of the greatest challenges for society and our industry in both the short and longer term. Whilst the escalating global temperatures are expected to intensify and bring more frequent heatwaves18, it’s reassuring that the impact on claim rates is likely to be minor. SCOR is committed to monitoring trends in extreme weather and their impact on human health so we can continue to manage this risk going forward.

1 Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Key Aspects of the Paris Agreement. Retrieved from UNFCCC

2 Science. (2022). Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple tipping points. DOI: 10.1126/science.abn7950

3 National Centers for Environmental Information. Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series. Retrieved from NCEI

4 World Economic Forum article. Climate crisis may cause 14.5m deaths by 2050. Retrieved from WEF

5 United Nations Chronicle. Climate Change and Malaria: A Complex Relationship. Retrieved from UN Chronicle

6 Liu, Jingwen et al. Heat exposure and cardiovascular health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Retrieved from The Lancet

7 Yash Desai et al. (2023). Heat and the heart. Retrieved from Pubmed

8 Anderson, B. G., & Bell, M. L. (2009). Weather-Related Mortality: How Heat, Cold, and Heat Waves Affect Mortality in the United States. Epidemiology, 20(2), 205-213. DOI: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190ee08

9 European Environment Agency. Combined Effects of Air Pollution and Heat Exposure. Retrieved from EEA

10 Gasparrini, A., et al. (2015). Mortality Risk Attributable to High and Low Ambient Temperature: A Multicounty Observational Study. The Lancet, 386(9991), 369-375. DOI: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)62114-0/fulltext

11 Jie-Fu Fan et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cold exposure and cardiovascular disease outcomes. Retrieved from PubMed

12 Satbyul Estella Kim et al. A nationwide population-based retrospective study in Japan. Retrieved from PubMed

13 UK Met office article. Effects of climate change. Retrieved from MetOffice

14 Met Office. (2022). What’s the Best Way to Map Mega-Heat?. Retrieved from Bloomberg

15 Office for National Statistics. Deaths Registered Weekly in England and Wales, Provisional. Retrieved from ONS

16 Office for National Statistics. Climate-Related Mortality and Hospital Admissions, England, and Wales: 1988 to 2022. Retrieved from ONS

17 Public Health England. Heatwave Mortality Monitoring - Summer 2018. Retrieved from PHE

18 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Chapter 11: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. Retrieved from IPCC