Phil

Cleverley

SCOR Chief Underwriter

29 août 2024

The NHS has recently announced that it will be offering more than 150,000 adults and children with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) in England and Wales advanced technological treatment in the form of “artificial pancreas” devices, which experts are hailing as a “gamechanger” that will “save lives and heartbreak”.

The artificial pancreas device, also called a hybrid closed loop (HCL) system, uses a hi-tech algorithm to determine the amount of insulin that should be administered and monitors blood sugar levels to maintain them at safe and appropriate levels.

A world-first trial on the NHS showed it was more effective at managing diabetes than current devices and is far less onerous for diabetics to use than traditional methods. It makes the UK a world leader in making HCL widely available, as England and Wales follow the lead of Scotland, who approved the use of HCL in 2022. Work is also under way to introduce HCL in Northern Ireland.

In Ireland, the health service provides insulin pumps free under the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Community Funded Schemes, and the consumable products are also free through the Long-Term Illness scheme. However, rollout depends upon hardware availability and the resources available to train people to use the systems is regionally variable.

A very small number of people that are not included by HSE have been able to get privately funded insulin pumps , provided there is support from an attending consultant. Irish Health insurers do not currently cover insulin pumps on Private Medical Insurance schemes.

People who have T1DM typically will use a treatment “loop” in managing the condition, which involves finger-prick blood tests to monitor blood glucose and the use of an insulin injector pen, or other method to inject insulin to control their blood sugar levels as needed. This requires intense management 24 hours a day. Some patients may also already use individual elements of the artificial pancreas, such as continuous glucose monitor or an insulin pump.

Hundreds of individual treatment decisions must be made around the clock as extreme blood glucose highs and lows can be fatal. Automating what is currently a manual process, the artificial pancreas lifts the relentless burden upon individuals and dramatically reduces the number of decisions users have to make on a daily basis.

The development of artificial pancreas is making a big difference to many people with T1DM by reducing the time spent dealing with diabetes on the go, improving sleep, reducing stress levels, and improving overall quality of life.

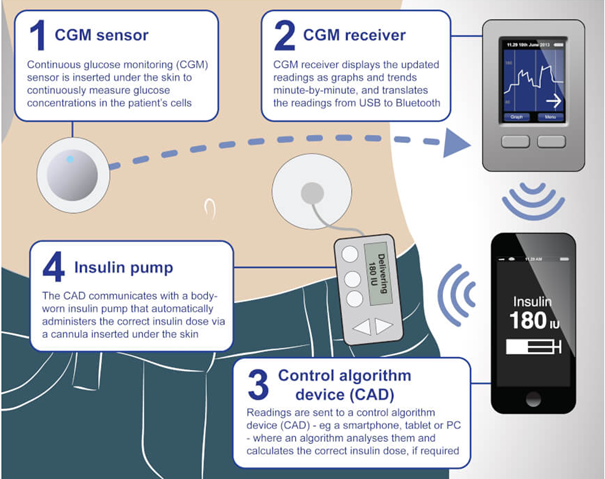

The artificial pancreas has been found to be better at maintaining optimal blood sugar levels and reducing the risk of the development of complications from diabetes. It works via a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) sensor attached to the body which continuously transmits data to a control algorithm device (CAD), usually a smartphone or iPad, that in turn informs a body-worn insulin pump that contains an insulin reservoir or is primed with insulin cartridges like those used in insulin injector pens. The pump then calculates how much insulin is needed with use of an algorithm to tell the pump how much insulin to deliver to the body based on the sensor's glucose readings.

However, HCL systems still require some human judgment. Fluctuations in blood sugar due to carbohydrate intake, vigorous exercise or extremes of temperatures can, in some cases, be anticipated by the patient, who could then make adjustments to the insulin dose as needed.

Final draft guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that people in England and Wales should benefit from artificial pancreas devices if their diabetes is not adequately controlled by their current pump or glucose monitor.

There are about 290,000 people living with type 1 diabetes in England and Wales. More than half of them will now become eligible because their diabetes is not controlled with their current devices.

NICE has agreed with NHS England that all children and young people, women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy, and people who already have an insulin pump will be first to be offered a hybrid closed-loop system as part of a five-year rollout plan.

The technology will then be rolled out to those adults with an average HbA1c reading of 7.5% or more and those who suffer abnormally low blood sugar levels. NICE guidelines recommend people should aim for an HbA1c level of 6.5% or lower.

NICE said that, due to the need for extra staff alongside specialist training for patients and staff, it had accepted a request from NHS England for a rollout over five years.

For those not eligible via the NHS plan, it is still possible to purchase an HCL system. Insulin pumps cost between £2,000 and £3,000 plus around £1,500 per year for the cannulas, reservoirs and tubing required for their use. A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) costs about £2,000 a year.

Whilst this is an expense outside of the reach for some people living with DM, it may still be attractive in view of the significant day-to-day advantages they bring, particularly with regard to making control of the condition much easier to manage. Therefore, there could potentially be more artificial pancreas devices starting to be used outside those that are NHS-funded.

In addition to artificial pancreas, there are other exciting developments relating to the management of DM. These include nonelectronic nanotechnology-enabled devices, such as microneedle array patches and hydrogel-containing catheters.

Insulin “inhalers” and tablets, novel devices which enable non-invasive insulin administration, are also in different stages of development and offer great value in the future of potential DM treatment.

Most importantly, it is anticipated that the development and increased use of HCL systems in treating T1DM, will have a beneficial effect upon life expectancy and morbidity.

Underwriters are already aware of the importance of controlling blood glucose and HbA1c which are very significant risk factors included in underwriting guidelines for DM. Therefore, the benefits of improved control that HCL will deliver, will in time result in improved underwriting terms for DM that will make protection products more attainable and affordable for people with DM.

With CGM being readily available, this effectively is a form of wearable technology that potentially could become available to help monitor control in order to obtain lower premiums.

An interesting aspect relating to the development of artificial pancreas is that it could impact some of the critical illness wordings that cover major organ transplant (MOT).

From the early days of critical illness product development, there has been awareness of potential for pancreatic transplants in order to treat diabetes. Considering the number of people in the population living with T1DM, this could have a significant impact in terms of increasing frequency of claims. However, with traditional treatments being so effective for the vast majority of these people, we have not seen the same urgency for pancreatic transplants as there is with other organs, where there is typically always a shortage of suitable organs.

Claims under MOT are rare. This is because of a shortage of organs being transplanted and also because of the impacts of underwriting that can identify many cases at application that could develop into organ failure that could result in an organ transplant. However, with the introduction of artificial pancreas being more widely rolled out, this could change, depending upon what cover is being provided under the specific wordings.

The Association of British Insurers (ABI) wording for MOT is as follows:

The undergoing as a recipient of a transplant from another person, of bone marrow or of a complete heart, kidney, liver, lung, or pancreas, or inclusion on an official UK waiting list for such a procedure.

For the above definition, the following is not covered:

The position here is very clear: in order to claim, there has to be a complete organ transplanted from a human donor. Therefore, the application of an artificial pancreas would not be covered. However, there are some wordings in the market that extend cover for MOT as follows:

The undergoing as a recipient of a transplant from either a human donor, animal or insertion of an artificial device, or inclusion on an official waiting list for any of the following:

For the above definition, the following is not covered:

This wording extends cover from the ABI wording with an intention to cover artificial devices, including those of the pancreas.

When looking closely at this wording, it states there should be a “complete” transplant of pancreas which is not the case. In addition, there are other important functions the pancreas performs that HCL/artificial pancreas does not perform, such as the production of enzymes that aid digestion. However, with the HCL devices being commonly referred to as “artificial pancreas” together with no specific exclusion, it makes a strong case for those using HCL to treat their diabetes being covered under this wording.

Claims assessors need to be aware of this development, particularly where products are offering cover for artificial pancreas. It is important for both adult and children’s cover, as many T1DM are diagnosed in childhood and adolescence.

Underwriters and claims assessors will be encountering increasing numbers of cases where artificial pancreas/HCL systems will be mentioned in the medical reports received at application or at a time of claim. Therefore, this article intended to provide a useful insight into this development.

As discussed here, there are important implications for CI product development and claims. Most importantly, artificial pancreas/HCL is going to make such a fantastic difference to those with T1DM in terms of quality of life and life expectancy.